By: The Rev. Nathan Jennings, Ph.D.

The seminary has benefitted so immensely from our BRSG Partnership these past few years, and I have been one of those beneficiaries.

I have many moments of professional transformation that come to mind, but one that stands out to me as I reflect on these years, is a more recent interaction. As we have brought on new hires, our faculty has broadened to include a wider Beloved Community. Nevertheless, we remain predominantly, and historically, a white institution. Dr. Stephen Ray’s contribution to formal and informal faculty meetings and gatherings expanded my heart and mind to be able to notice, identify and address more faithfully those moments and situations where my non-white colleagues may be “taxed” unnecessarily due to the diversity they bring.

He helped guide me, personally, to see how things that seemed innocuous to me, as a white member of a predominantly white faculty, might impact my non-white colleagues in a significantly different, and potentially negative way. And that they, in turn, might not notice things or pick up on certain cues that would seem obvious to me. Being a good colleague, and sometimes senior colleague, must mean noticing things, and addressing them – appropriately. It also means celebrating the communities my colleagues represent beyond my own predominantly white and Episcopalian community. I feel inspired by this challenge.

The most significant impact that Dr. Stephen Ray made on me was more personal and theological in nature. I was formed, academically, at Yale Divinity School and at the University of Virginia in Post-critical approaches to theology and in the Radical Orthodoxy school of thought that was strong in the late ‘90s and early 00s. The Yale School “Post-critical turn,” was one that retrieved tradition without seeing critical scholarship as contrary, but as complimentary to the task of theology. Meanwhile, Radical Orthodoxy, formed me in a general “high church” ethos within Anglicanism that sought to address issues raised by continental social theory from a vigorous retrieval of the Augustinian heritage of Western Christianity.

This formation often made it difficult for me to know how to engage the theologies of other, and especially oppressed groups. From my focused point of view, these theological approaches did not acknowledge or understand the Christian tradition I felt formed by and committed to.

Dr. Stephen Ray was formed at Yale during the hey-day of the Post-critical turn. We were able to link up in that way. One of my advisors at UVA, Eugene Rogers, had been a peer at Yale with Dr. Ray. Formed as he was in these same approaches to theology and to the Christian tradition, Dr. Ray addressed my concerns and confusions and guided me to approach the issue in renewing ways.

When I say that the Post-critical turn retrieved “the tradition,” whose tradition were we talking about? He helped me to see that, for those on the margin, what I perceive to be “the tradition,” may be something they have never been formed by, had access to, or been allowed to use as resources to address their own theological and political needs. They may well see my “tradition,” as merely another tool of enforcing the predominant culture. And the response of many Post-critical scholars and Radical Orthodox theologians has not helped, as they can at times be dismissive of discourse that did not seem grounded in the tradition that they recognized.

Dr. Ray did not ask me to leave my own formation behind. My conversations with him have both challenged me and encouraged me. Perhaps there are resources in the traditions of the church of western Europe, especially those who fought to offer a counter-narrative to that of colonization and slavery, that can empower and help the marginalized and oppressed. How can I do my part to stop the cycle of making those already marginalized or oppressed encounter the theology I love as something merely “white”? How can I listen, deeply, to the encounter that the marginalized and the oppressed have with God? How can I show how the tradition in which I was formed has resources for freedom, justice, and peace for the benefit of all God’s children, and not just those with power?

As we move forward in our commitments, these questions will stay in my heart and on my tongue as I do my part to contribute to Beloved Community here at Seminary of the Southwest.

Questions to consider:

For those of us who are members of a traditionally empowered church, how can we do our part to stop the cycle of making those already marginalized or oppressed encounter the teachings and theologies of our traditions as merely “white”?

How can we listen, deeply, to the encounter that the marginalized and the oppressed have with God?

How can we show one another how the traditions in which we have been formed can join together to provide resources for freedom, justice, and peace that benefit all God’s children?

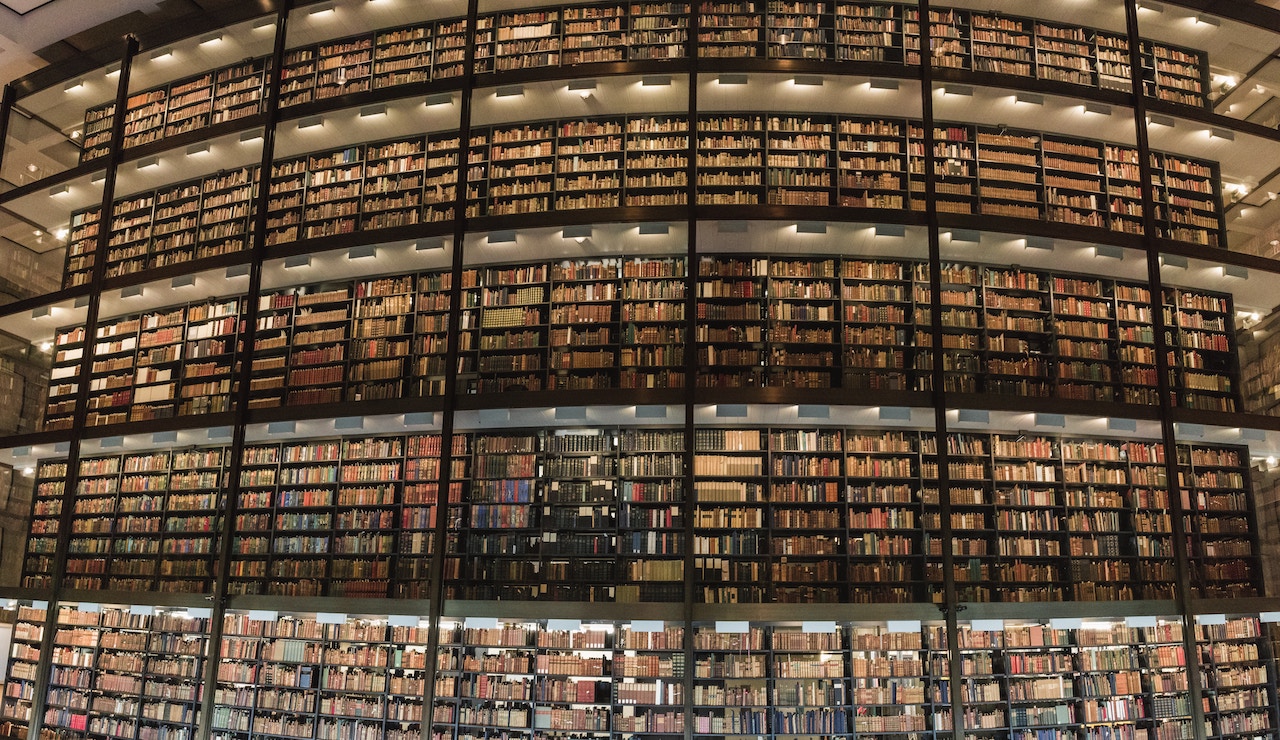

*Photo is of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University.

This fall, Sowing Holy Questions reflects on the personal and professional impacts of the Black Religious Scholars Group Visiting Professor partnership of the past five years.