An earlier version of this essay appeared in the Doing Good Together Faith Column of the Austin American Statesman in May of 2021.

This pandemic was supposed to end with the vaccine roll out, when we could all shed masks and great one another in public spaces again. Instead we’re awaiting the news that our children are eligible for the vaccine, and watching in grief as the “pandemic of the unvaccinated” along with “break through infections” keep putting our friends and family in the ERs and keep our celebrations on hold.

Even as we wait, though, the question we’re all asking, in one way or another, is how we will move forward when Covid-19 has become a manageable part of the array of viruses that we prepare ourselves for annually.

We’ve gotten used to relating to one another in Zoom boxes at our dining room tables. It has even become difficult to let go of identities forged in the last 18 months. If I take a walk in the park without a mask, what will people assume about me? What if I choose outdoor seating at a cafe? We have nearly forgotten how to be together without heavy layers of self-consciousness.

Communities of faith can play a role in helping us find the path forward. In fact, if a key point of disorientation during the last year and a half was a loss of embodied connection, the practices and teachings of Christianity may be one of our greatest resources.

We tend to think of faith groups as collections of people who think a certain way or believe a certain way. In fact, they are more immediately people who gather and use their bodies in a certain way. These communities operate within very physical rituals: think of gathering for prayer or the study of texts, or of the bodies involved in a baptism or marriage. Imagine an imam driving to a hospital to visit a sick member of their mosque. These activities are not extracurricular to a religious life; they are how religious communities create habits that help us navigate embodied life together.

This is what we need to start practicing again. Not that we haven’t found new ways to connect at a distance: we’ve made technology work for us like never before, and found new ways to look at each other’s faces and laugh with faraway friends. But let’s not forget that being together without physical presence is always going to feel incomplete.

One important teaching of traditional Christianity is that our souls and bodies will be united in heaven. This is especially a difficult teaching for modern believers, after René Descartes convinced us that humans are essentially invisible “thinking things,” and that the body is a nonessential “extension.” But theologians have, since long before Descartes, insisted that to fully enjoy the presence of God we would need a body and not just a soul. Thomas Aquinas argued in the thirteenth century that after their death, humans enjoy God’s presence in a real but incomplete way. In that state we are waiting for the day of resurrection when we will be able to use our bodily senses to “taste” the divine being. Until then disembodied souls are, to borrow from Stranger Things’ Eleven, only “half-way happy.”

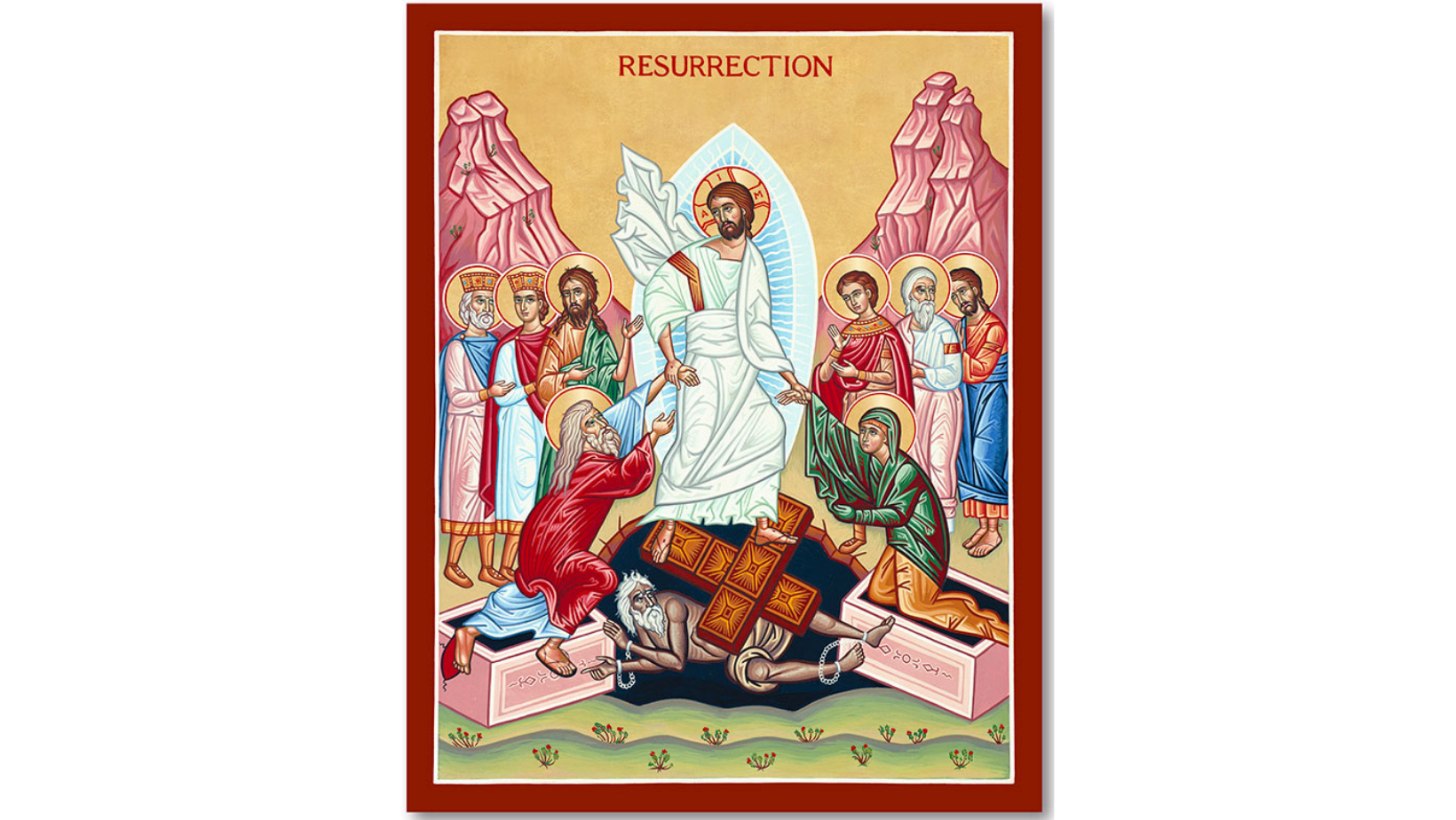

To recall this odd ancient religious teaching—that graves will be opened and the dead bodies will rise to meet God so we can enjoy the fullness of our created being—is one way of challenging ourselves to relearn how to be a body alongside other bodies. Teachings and rituals like these could become a way of calling ourselves back out of isolation: an isolation that was, for a time, a deeply important way of caring for one another.

We can honor the important decisions we made during this long stretch without forgetting that we were created for more than this compromised connection. We were made for embodied togetherness. For hugs, for feasts, for long walks holding hands, and deep conversations with new acquaintances. That’s the world I continue to believe in. The world that many religious traditions insist has no end. And it’s the world I’m ready to relearn.

This fall, Sowing Holy Questions reflects on pandemic re-entry, with emphasis on the theological, equity, and/or mental health ramifications of living in these times.

4 Responses

Thank you for this. Feeds my soul.

Thank you for that response, Kathleen.

Thank you for this. My faith stands strong.

Tony, I love your meditation and will likely tuck it into a that I use for morning devotions, just to re-read it from time to time. I also love the icon you posted at the top of your article. It’s other name is “The Harrowing of Hell” and I preached on it at the Easter Vigil in 2017, I think. I am including a link to information behind the icon that I found fascinating and useful in preparing my sermon.

https://www.orthodoxroad.com/christs-descent-into-hell-icon-explanation/

In Peace, Liz Hendrick+