Matt Matthews

My nephew Nathan David, 46, died Monday night. There will be no funeral. No one will lead a litany of thanks, pray one plea for balm, or utter even an obligatory alleluia of hope. Survivors will mark this passing mostly alone, separated by many cold miles.

Nathan erased himself with alcohol. Who can blame him for blaming it on the bodies of women and children he saw piled by a roadside in Iraq during the war? Trauma changes us. The hurt was cumulative, like plaque on molars. Twelve beers a day and a few packs of cigarettes eased him into the blur of deepening pain.

He disappeared from us inch by inch. As a younger man, he showed up in outrageous swings of optimism. He tried bumming money off me once to enroll in golf school. He often appeared to his poor parents in miserable storms of rage, stupor, and helplessness. The VA, his folks, and well-meaning others heaved whole coils of lifeline, none of which he could grasp for long. The drowning took a quarter of a century.

While he left behind little more than skid marks, he was young once—funny, gregarious, and warm—and held the hope of a million suns as do all our sons and daughters.

He was born in 1978. The soundtrack for Saturday Night Fever topped the music charts. His name derives from Old Testament Hebrew and means he gave or gift of God. As a child, we celebrated him as a gift from God. When disease obscured and overtook him, how he might have been a gift was unclear. I didn’t know what to do with my nephew after he grew up.

I was a teen when he was born. I roomed with his family my sophomore year at VCU. He was seven. Their Richmond apartment was small. My study was a closet, and my typing reverberated through the rooms. I remember family meals with him and his parents and his older brother, Adam. For a brief season, my brother-in-law Bill cracked open the dictionary at the dining table and we’d learn the first obscure word we randomly found. I’ve employed the word myriad ever since.

My life was running a hundred miles per hour, so I remember little. I remember when Nathan cried, he cried big tears. And I cannot forget that unforgettable, freckled smile. He was exuberant, eager to play, and always glad to see me.

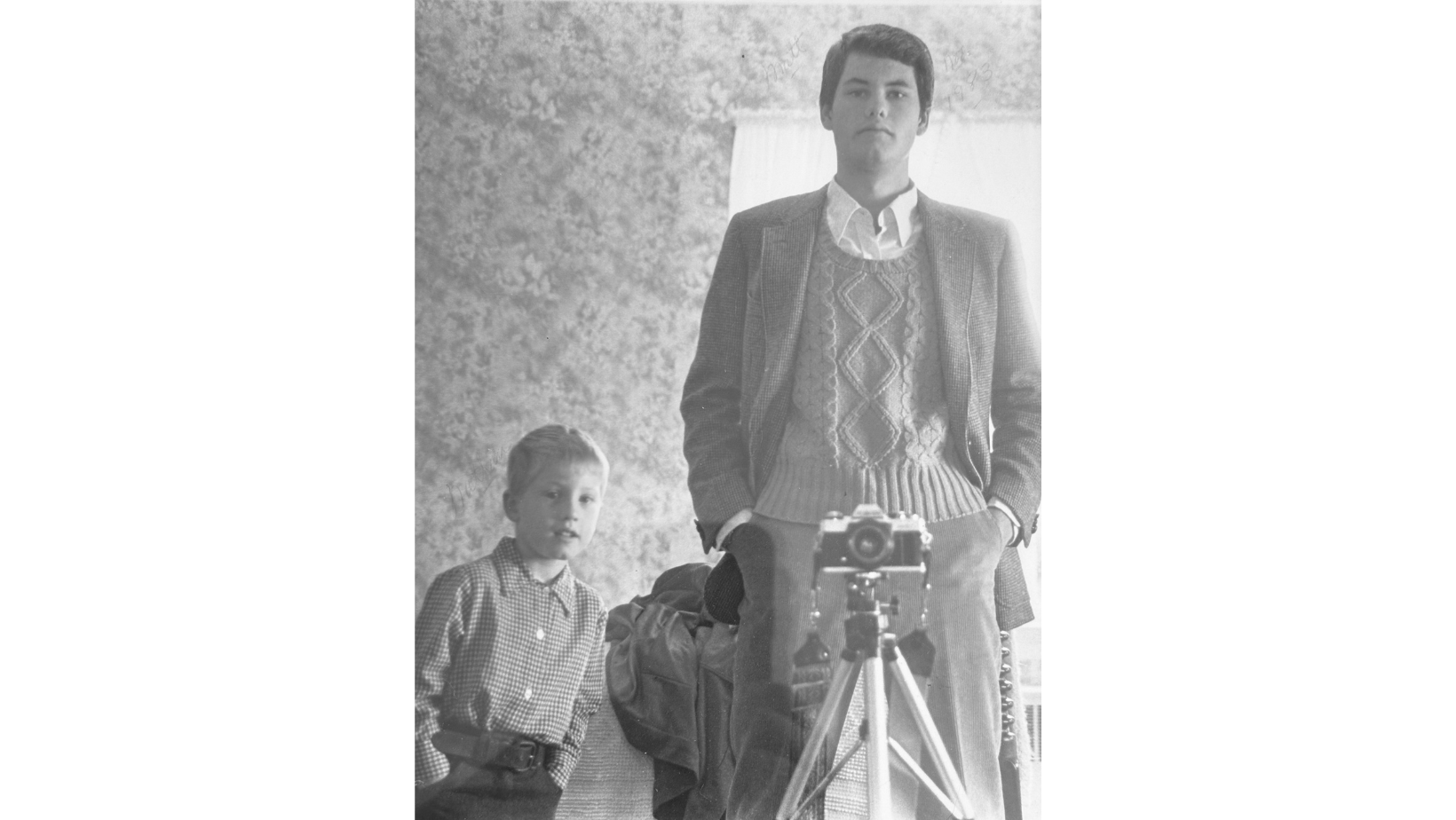

That year I took a photojournalism class. We were assigned to shoot a self-portrait. I affixed my Minolta on a tripod and stood before a floor-to-ceiling mirror. I decked myself in tweed, Oxford shirt, cable-knit sweater, and creased cords. I set the timer, clicked the shutter, and stood like a Sphinx awaiting the few seconds for the picture to snap.

Out of the edge of my vision, I saw Nathan stepping into the room. Through my clenched teeth, I told him to stop. He was going to ruin my picture, and film in those days, even black and white, was expensive on a college budget. Nathan couldn’t fathom what was happening. His Uncle Matt was frozen with his hands in his pockets looking into a mirror. What was he looking at? He put his little hands into his own pockets—his uncle’s doppelgänger—and eased into the room. I hissed. Stop. He oozed in, anyway, leaned warily towards me, and studied the mirror I was looking into.

After the picture clicked, I hollered at him. This may have occasioned a bout of those largish tears. In those days, it was all about me, which, unfortunately, hasn’t changed much. I banished him from the room. I took a few more shots.

My proposed final picture had me standing stiffly alone. The threads and the camera made the man. At 19, I was sharp.

But the prof looked at my contact sheets and said, “That’s the picture.”

He pointed to the single shot Nathan had photobombed. And for the first time, I saw its accidental genius.

That seven-year-old with the checkered, button-down shirt looked entirely dapper himself. His belt, an obvious hand-me-down from his older brother, was too long. But the light nicely side-lit his face. A dot of shadow clefted his chin, identical to the shadow that clefted my own. He leaned into the frame, hands in his pockets, my mini-me wanna-be replica.

I submitted this unintended masterpiece, which captured tension, drama, and action, for my final and aced the class. Nathan’s interruption vibrated life into an otherwise dull shot.

That photograph has been framed on my wall for almost 40 years. Its ever-yielding truths are myriad and layered. A big lesson is we aren’t who we are without each other. The interruptions in life are where life actually happens. We grow up and old fast. Somebody might be looking up at you; don’t let them down.

And that old picture judges me. I look at it and see the happy little boy I dared to shoo away. That truth

shatters me.

Nathan’s adolescence was turbulent. His family moved a few times. He dropped out of high school. Joined the Army. Deployed to the Gulf. Got married. Got divorced. Got out of the Army. Got a girl pregnant. He never found his feet.

I had my own life to figure out. I watched Nathan’s from high up in the bleachers, far removed from the action as Nathan became an unrecognizable and smaller and smaller speck on the field of life.

Two days after my sister Susan texted me with the news, I cracked open my late mother’s calendar box to record his death date. I was astonished to be reminded that my father died that same day 23 years before, on Epiphany. Uncle Bob died the day after, 41 years ago. My grandfather, whom we called Deda, died a week later, on the 13th, in 1972.

Here were so many deaths recorded in the first two weeks of bleak January. On that same page, also written in my mother’s hand, were family birthdays. Ryan Whitcomb, seven pounds, 15 ounces. Bob Palmer. Megan Remaley.

The births outnumbered the deaths.

I found myself reaching out for the hands of these living and dead. I wanted to thank God for my nephew, and I couldn’t bear to do it alone. They all generously stepped in. Deda nodded. It was good to see my dad again. Nathan himself eased quietly into the circle; I didn’t shoo him away this time. His hand was warm and steady. When we said “Amen” together, his voice rang clear and strong.

4 Responses

Hello Matt,

Thank you for sharing your soulful memories of Nathan David. I noticed that both you and I attended VCU in 1978. I graduated in 1980. My poem, “Redneck Liturgy” also mentions Richmond, Virginia. I grew-up there. Blessings to you and your loved ones.

Hi Sharon, I was Mass Com, 1986. I loved VCU and Richmond. 🙂 M

What a revealing piece of not just Nathan David but of you. As I celebrate my granddaughters 2nd birthday, I am still morning my brothers recent death and the love and disappointments that traveled the years of that relationship.

That’s nicely put, Jean: I am still mourning my brother’s recent death and the love and disappointments that traveled the years of that relationship. A chaplain friend told me I shouldn’t think for one minute that my father’s death signaled the end of the relationship. I had no idea what he meant then. I think I do now. May it be so with your relations with your brother.